In the 19th and early 20th Centuries, many African Americna and immigrant families became homeowners by a practice called “contract for deed,” which involved no mortgage. Prevalent in the Deep South and urban neighborhoods, African Americans often were caught in the onerous contract for deed arrangements in Chicago in the 1950s through the 1970s. In the mid-20th century contracts for deed were common in response to bank redlining, the practice of refusing to make loans in minority neighborhoods.

Yet in recent years, non-profit groups have used a similar model as a tool to help prospective buyers who cannot qualify for a traditional mortgage or who don’t trust the financial system. But the practice also smacks of oppression of minorities, and historically it echoes schemes popular in the Deep South and among the urban poor.

Contracts for deeds are not new. A 2009 book by the historian Beryl Satter, Family Properties: Race, Real Estate, and the Exploitation of Black Urban America,

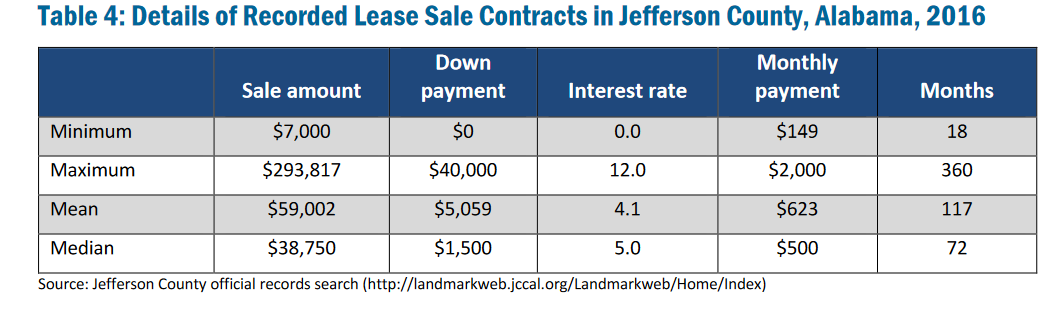

New research by the Atlanta Federal Reserve found that during the darkest days of the housing crash, investors and lenders in several Southeastern markets dusted off the contract for deed to sell foreclosures when buyers were hard to find. The practice disappeared by 2014, but the researchers found that some of the sellers set large down payments, high monthly amounts and even required interest payments from sellers who risked losing everything if they failed to make a single payment over terms as long as 20 years.

A contract for deed requires buyers to pay monthly installments on homes they receive. The buyer is responsible for bringing the home, which is often in disrepair, up to habitable standards within a few months. Failure to repair the house, or missing a single monthly payment, means the lender takes back the home. The buyer in these transactions builds no equity in the home and does not receive the deed until the last payment is made.

The Atlanta Federal Reserve began researching contract for deed transactions in the Southeast following reports that Wall Street investors were making large purchases of foreclosures in Georgia and Alabama between 2010 and 2011 and selling them with the contract for deed model.

The Atlanta Fed researchers focused their efforts on Jefferson County, Alabama, home to Birmingham. In Alabama, full data on recorded contract for deed sales were available. They found about 10 percent of contract for deed sales (or “lease sale contracts”) were made by institutional, corporate investors and the rest by individuals. Some were, in fact, good deals that presented little risk to buyers, particular transactions with no down payment and low or zero interest. Others demonstrate unfavorable terms in subprime interest rates, balloon payments, and other untenable contract stipulations.

The corporate contract for deed sales increased from 2008 to 2013 and had plateaued or declined since that time. These properties tend to be located in majority African-American neighborhoods with less access to financial services. However, a much larger yet unknown number of contracts for deed involves a small-scale seller, such as a private individual or local firm. The terms of these contracts vary, with roughly equal numbers of seemingly low-risk contracts and with extremely high-interest rates and unfair forfeiture clauses.

Ann Carpenter, senior community and economic development adviser at the Atlanta Fed, calls the concentration in minority neighborhoods “very troubling,” as the abusive practices of some landlord-sellers help perpetuate racial and class gaps in wealth. Though the unfavorable arrangements by corporate investors have received considerable attention, the paper finds that a larger number of contracts for deed involve small-scale sellers such as private individuals or local firms. The terms of contracts vary, with roughly equal numbers of seemingly low-risk contracts and contracts with extremely high-interest rates and unforgiving forfeiture clauses.

[ad_2]

Source link