On June 24, 1997, a pedestrian crossing Highway 111 north of the Salton Sea was run over by a vehicle and died. Every attempt to attach a name to the man, including submitting his fingerprints to federal agencies, failed.

More recently, on July 7, 2011, a man with 20 cents in his pockets but no identification was fatally struck by a train under the Ivy Street overpass in Riverside. Again, as in the case of almost 60 other people, the Riverside County Coroner’s Office had a face but couldn’t match a name.

But those fortunes changed this year when the FBI Laboratory in Quantico, Virginia, began applying an existing fingerprint identification technology in a new way. As a result, the families of 195 unidentified people across the country, including the two in Riverside County, now know what happened to their loved ones.

A family in Mexico heard from co-workers of Mexicali resident Mario Alberto Ortiz-Vicente, 32, that he had been in an accident, but the family didn’t know where. They filed missing-persons reports in Kern and Imperial counties on the relative who would occasionally come to the U.S. to work. Now, they know that he died, and where.

“(The) family was extremely relieved to finally be provided answers and closure in the search for their loved one,” a Sheriff’s Department news release said.

And a family in Oregon now knows that Lawrence Michael “Larry” Wilhelm, 57, a transient who popped in and out of their lives, was finally at rest.

“The unimaginable success of this has been astounding for us,” said Bryan Johnson, a major incident management program manager in the FBI’s latent print support unit in Virginia. “It’s been heartwarming.”

But the news of Wilhelm’s location, and death, was bittersweet for his relatives.

The last time that sister Nancy Wilhelm heard from her brother was in the 1990s, when he announced that he had HIV and was headed to Amsterdam.

“He basically moved away, and nobody in our family knew where he went,” said Wilhelm, who lives in Springfield, Oregon. “He wasn’t missing to us because he was missing so long. He lived a very private life.”

Larry Wilhelm took a job with a phone company in Seattle out of high school and was rarely seen.

“He’d always pop back into Mom and Dad’s life when he needed something,” his sister said.

Nancy Wilhelm said the notification of Larry’s death on June 19 gave the family “closure, I guess.”

A new tactic

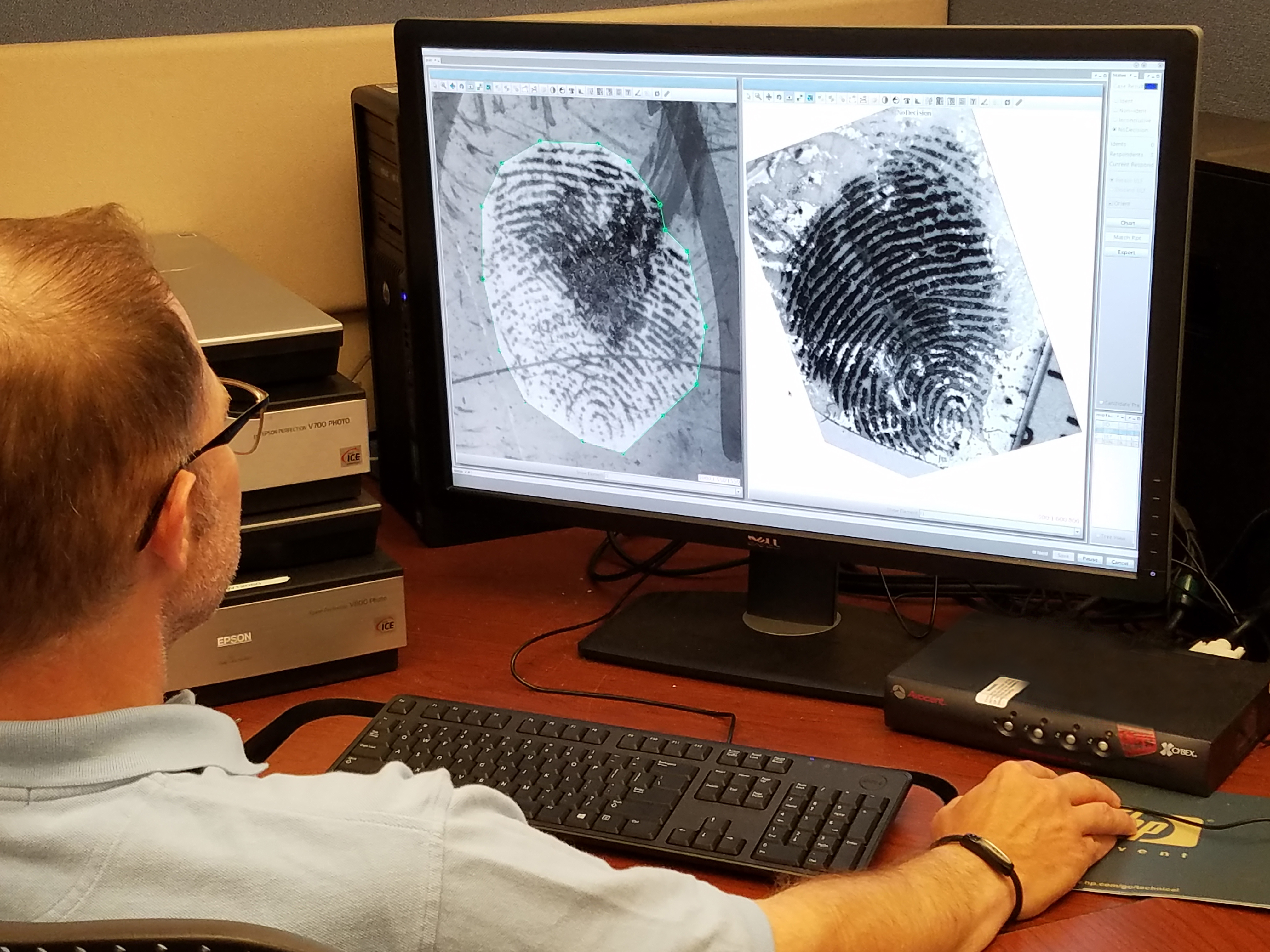

In the cases of deceased persons, the FBI receives a card with the prints of 10 fingers that is run through a computer and its database. The algorithm is designed for prints that are in good condition.

“That usually does work” in producing an identity, Johnson said. “However, with the deceased individuals, a lot of times their bodies may not be in great condition, so the prints may not be in great condition.”

The U.S. Department of Justice’s NamUs – the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System – had a collection of such cards with hard-to-read prints. The FBI lab obtained 1,500 of those cards and had 35 specially trained examiners look at the prints, one finger at a time, using a different algorithm and a larger and more accurate database, Johnson said.

He described the examinations as “more focused and accurate.”

“Human interaction is one of the biggest changes,” Johnson said.

The re-examination began in February and has identified 195 people in 26 states. The oldest case was from 1975.

“We have heard back from coroners, and they’re extremely thankful and happy with the results, because they work day in and day out with limited information,” Johnson said.

Kimberly Edwards, unit chief of the FBI’s latent print support unit, encouraged coroner’s offices not to give up on unsolved identity cases.

“We encourage people

with older records (to submit them). It’s worthwhile trying again because of the advances in technology,” she said.

By the numbers

1,500: Number of cards with 10 fingerprints on them that the FBI examined one finger at a time.

35: Specially trained examiners looking at the fingerprint cards.

197: Number of people identified through this process.

26: Number of states in which someone has been identified.

1975: Year of the oldest case solved.

[ad_2]

Source link